|

|

CAP 201a - Computer Animation I

Lesson 3 - Chapter 5, Animating a Ball

and Chapter 6, Animating a Thrown Knife

Objectives:

Chapter 5 introduces the use of the time

slider, keyframes, and the curve editor. Objectives important to this

lesson:

- Frames, key frames, and in-betweens

- Animation: bouncing ball

- Track editor-Curve editor

- Tangent types

- Squash and stretch

- Layering animation

- X-form modifier

Chapter 6 continues the lesson on using the

curve editor. Objectives important to this lesson:

- Trajectories

- Anticipation

- Momentum

Concepts:

Modeling is a vital skill in computer animation, but so is

animation itself. In our previous texts from these authors, animation

was introduced in earlier chapters with simple projects. These have

been eliminated in this text. We will continue at this point with Chapter

5 to introduce the basic animation tools and to actually animate

some objects.

It has been a while since you should have been exposed to some

basic terms, so let's review them:

As they have done before, the authors ask you to copy the project

folder for this chapter to your working area, and to set

3DS Max to use that as the root folder for this project.

For the exercises in these projects, you will want to have Auto

Key turned on before you make changes to objects in the scene.

The Auto Key feature automatically captures key frame information for

common changes to objects, but only when it is turned on.

Project: the Bouncing Ball

This project includes a series of exercises to animate a

bouncing ball in several ways. Begin as indicated on page 111, by

- copying the project file from your download or from the class resource

drive to your working area,

- and setting 3DS Max to

use that as the root folder for this project.

Project Exercise 1: Animating the Ball

The exercise starts by telling you to open a scene file. Find

it and open it in 3DS Max. The text says that you will be working on

the gross animation for the scene first. Setting the

gross animation is also called blocking the scene,

which may be more familiar to you if you have been an actor. If neither

term is familiar to you, you will be working on the major

movement of objects (and characters, if the scene had

characters). Sometimes programs refer to both objects and characters as

actors, since both can be animated in a scene.

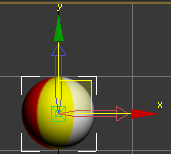

The scene contains a ball object. In

step 1, you adjust its pivot point. Select the ball, then open the Hierarchy

panel, choose Pivot, and click the Affect

Pivot Only button. Move the pivot point to the bottom of the

ball, then turn off the Affect Pivot Only

button. The scene contains a ball object. In

step 1, you adjust its pivot point. Select the ball, then open the Hierarchy

panel, choose Pivot, and click the Affect

Pivot Only button. Move the pivot point to the bottom of the

ball, then turn off the Affect Pivot Only

button.

Pivot points can be located outside the objects they affect, so be

careful not to place the pivot point outside the ball in this step. - The time slider is used to move forward

and backward in time for an animation. It should be at frame 0

by default. Don't move the time slider yet.

- Turn on the Auto Key feature (by clicking

the button that says Auto Key) and now drag the time

slider to frame 10. (The currently selected frame

number is displayed on the slider.)

- Click the Select and Move tool, and

select the ball. Move the ball to 0

on the z-axis with the mouse or with the transform

type-in box at the bottom of the interface. This should result

in a keyframe at time 0 and at time 10. I had you

turn on Auto Key before moving the time slider to capture the initial

position of the ball, not just the second position. In this version of

the program, this precaution may not be necessary. In previous

editions, it was a good idea.

- The text starts its numbering over again. I will not do so

here. You should turn off the Auto Key function now.

In frame 20, you want the ball to go back to the same

position it was in originally at frame 0.

The text sensibly recommends that you copy the keyframe in frame 0 by

selecting that keyframe (click it on the

timeline), holding down a shift key, and dragging

the keyframe to time marker 20. Note that this does not result in a

dialog box about making a copy or an instance or a reference. Copies of

keyframes are just copies.

- You should scrub the time slider to check the movement so

far. (That means you drag it left and right to see the animation.)

The text turns to the idea of turning a few frames into a repeating

cycle by using a tool called the Track View Curve

Editor. (The Track View tool has another editor, the

Dope Sheet, which is not used in this chapter.)

Project Exercise 2: Introducing the Curve

Editor

The exercise starts on page 114.

- Make sure the ball is selected. Use this

menu sequence: Graph Editor, Track View,

Curve Editor. You should see a screen

something like the one on the bottom of page 114.

- Look at the illustrations on page 115, regarding step 2.

Find the Controller menu, open it, and click the Out-of-Range

Types button. (And pause to wonder what kind of person named

it that. If someone suggested that name to me, I would have asked them

to call it the Extrapolate Curve button. That's what it does.) As the

exercise notes, the Out-of-Range part of the name refers to extending

the curve beyond the range of the first and last keyframes.

- Once you have clicked the button with the awful name, you

will see a dialog box with a worse name (Parameter Curve

Out-of-Range Types) that lets you choose one of the six ways the

program knows how to extend the existing curve.

Question 1: What are

names of the six types of curve extensions?

For this exercise, click Loop, then click OK.

- Note the dashed line in the curve editor

that stands for the extrapolated curve. (To extrapolate means

to predict what would happen if something were to continue. Anger at the program is not the only reason to increase your vocabulary.)

The features of the Parameter Curves are

discussed on pages 116 and 117. Two more related concepts are

introduced: ease-in and ease-out.

These features can be applied to any keyframe. They mean that the transition

into or out of the keyframe can be made more gradual

and less abrupt.

Page 118 brings up the concept of gravity, as it applies to a

bouncing ball. The animation does not look realistic yet, because a

real bouncing ball moves faster as it approaches the bottom

of a bounce, and moves slower as it approaches the top

of a bounce: down is working with gravity, up is fighting gravity.

Our ball is moving at the same rate at the top and the

bottom of the bounce. The text introduces a new technique to handle

this problem, using the Curve Editor again. (This time it uses the Mini

Curve Editor. Don't be confused by that. It is just smaller

version of the Curve Editor that leaves more of the viewports visible

than the larger Curve Editor.) The text refers to the thing you will

edit next as a tangency. A tangent is a line that

touches a curve at one point. In a sense, the keyframes

touch the curve of change for an object at one point

on that curve. What you are editing is the way the

keyframe is attached to the curve. The default kind of tangent for a

keyframe is Smooth, which moves into and out of the

keyframe at the same rate.

Project Exercise 3: Changing Tangency Type

In the procedure on page 119, you change the tangency of the

keyframe at the bottom of the bounce to Fast.

This makes the ball speed up near that keyframe. You leave the

tangencies at the top of the curve Smooth.

The effect of this is to make the ball "less fast"

when it is near a Smooth tangency, and "more

fast" when it is near a Fast tangency. Make

the changes indicated in the text.

The text changes topics again on page 120, explaining that the

ball should also be compressed a bit at the bottom of a bounce, and

it should extend (elongate) a bit at the top of a bounce. The two

concepts are called squash and stretch.

Project Exercise 4: Squash and Stretch

- In step 1, select the ball and turn on

the Auto Key feature. You are told to

turn on the Mini Curve Editor and drag the Track

Bar Time slider to frame 10. Before you do this,

take note of something. Turn the Mini Curve Editor off,

and move the Time Slider on the scene timeline to Frame

10. Now turn on the Mini Curve Editor and

check the position of the Track Bar Time

slider. It looks like it is on Frame 9, not

10. The scene timeline and the Mini Curve Editor do not appear to use

the same numbering scheme. Take this into account as you use the Track

Bar Time slider.

After you move the slider, you are told to access the flyout

for the Scale tool and choose the Select and

Squash mode for the tool. (A tiny picture appears on page

120.) The instruction after that picture is poorly worded. What you

should do is place your mouse pointer over the blue handle (z-axis

handle) of the transform gizmo that appears on the ball. Watch the

values change in the type-in transform boxes at the bottom of the

interface as you drag that handle down. You want the value for the

z-axis to be about 80. (It is practically impossible to be exactly

80 unless you enter that number manually.)

Note that the other values go up as the z-axis value decreases. The Select

and Squash tool maintains a constant volume

for the object, so as z is decreased, x and y increase. Get a balloon,

blow it up about half way, then play squash and stretch with it. You

should get the idea quickly.

- Step 2 tells you to move to Frame 0. Drag

the z-axis handle again, this time to increase the z value to

about 120.

- The text tells you that you could shift-drag

keys to copy them from one position to another on the

timeline. Since the Mini Curve Editor is blocking your view of the

timeline, it is good that you can copy the keys in the Mini

Curve Editor (or the Curve Editor) as well.

- First, select the Scale track in the Controller

window.

- Second, find the Move Keys tool in

the Mini Curve Editor's toolbar.

- Access the flyout for the Move Keys

tool as indicated in the text, and change it to the Move Keys

Horizontal tool. You will use this tool in a minute.

- Drag a selection marquee around the

indicated keyframes located at frame 0. (You do not need a special tool

for this. Just drag a rectangle around them with your mouse.) You can

now shift-drag any one of those keyframes to copy it

to frame 20, and the others will be copied there as

well.

- Use the Mini Curve Editor's menu bar to

select Controller, Out-of-Range Types.

Click Loop, and click OK. Test

and save incrementally.

The next problem is with the timing of the

squash and stretch events. 3DS Max has automatically calculated in-betweens

that assume a constant transition from one state to

another. This is not realistic: the ball should not

squash before it meets the floor, and it should recover immediately

upon bouncing. (You should realize that the squash and stretch effects

used in this scene are exaggerated, but we still want some

realism.)

Project Exercise 5: Setting squash and

stretch timing

(From page 122: "...follow these steps as if they were law." I beg

your pardon? I know comedy is difficult, but come on.)

- Close the Mini Curve Editor. On the

scene's timeline, put the time slider at frame

8. Make sure Auto Key is on. Use the Curve

Editor (not the Mini Curve Editor) for the next steps. Locate

and select the ball's Scale track. (The ball has to

be selected first.) Find and click the Insert

Keys button on the Curve Editor's toolbar. Click a Scale

curve at the marked frame. A new keyframe appears on all the Scale

curves. The book notes that only two curves appear because x and y are

the same values.

- Examine the picture on page 122. Find the

two type-in boxes indicated in that picture. The left

box is for the frame number, and the right

one is for the value to use at that frame. You should

be on frame 8 at this time. Enter 100

in the right box to set all the selected Scale curves to 100% at frame

8.

- In step 3, you are instructed to move the time

slider to frame 12, add new keyframes, and

to set the curve values to 100 at

that keyframe as well. The effect should be to make the ball squash

only for a few frames in each cycle.

- Turn off Auto Key and test.

Change if necessary, and save when it is right.

On page 123, the text discusses adding a forward

motion to the ball. It refers to adding this

motion at this stage as layering animation. This does

not mean that you are using layers as you might

in a Photoshop image. It just means that if often makes sense to get

one kind of animation right (like a vertical bounce)

before you add another kind (like a horizontal movement).

This method requires that you think about animation

like an animator (or a physicist) instead of like an audience member.

You need to plan the different kinds of motion that

will be needed for the scene, and assign values to each part of it

across time. Of course, this would be easier to do if someone

had provided a story board of the planned animated scene to us.

You have already made the ball bounce up and

down. Adding a forward motion

in the same time sequence will make both

motions happen at the same time. You could make the two

motions sequential by having them happen at different

times. That is not what we want. We want the ball to bounce

as it moves along a path. It is useful that you can

add the up and down motion, then add the left

to right motion, and you will get the resulting arcing

bounce motion without having to calculate the arcs. (You will,

however, need to fine tune it. Animation is not totally automatic, else

you wouldn't be needed as an animator.)

Project Exercise 6: Moving the ball

forward

- This one starts on page 123. In the scene, move the time

slider to frame 0. Click the Select

and Move tool, then click the ball. Right-click

the Perspective (Camera) viewport to select it. Move

the ball to the left as noted in the text, which will be a change of

about -30 on the x-axis.

- Move the time slider to frame 100. Turn

on Auto Key. Move the ball to the right, to about +30

on the x-axis.

- Open the Curve Editor. Find and select

the x-Position track.

- The text informs us that keyframes were automatically

created on the x and y Position

tracks when you created the up and down motion. Those

keyframes were placeholders. Find the keyframes on

the x-Position track at frame 10 and frame 20.

Select them (click them) and delete

them (press your Delete key).

- Click our now-familiar friend, the Out-of-Range

Types button. (The text calls it the Parameter Curves

Out-of-Range Types button. It used to be called that, now its

name is two words shorter. Aren't you thrilled?)

Choose Constant and click OK. Turn off

Auto Key. Note the shortcut key for playing the

current animation: /. (This is the slash

key, not the backslash key. If you call it by the wrong name, it will

become angry.)

- Note the shape of the curve in the Curve Editor at this

point. Its ends (at frames 0 and 100) indicate an ease out

and ease in at those points. This is the default

tangency at work. You want to change this. Select

both keys in the Curve Editor (with a marquee?) and click the Linear

Tangent button. Or would an ease out make sense for

the first one? Objects do not typically accelerate from 0 to x

instantly, do they? The answer depends on the scene. Did someone toss

the ball? Ease out of the frame. Did a ball suddenly appear from a rift

in space/time? Is it already at full speed, having travelled some

distance before we saw it? Use a linear tangent.

This is a good place to pause and save

again. Remember to save your file with a new, incremental

name, so you have more than one place to go when you need to go back in

time.

On page 124, the text addresses a problem it

created back at the beginning of the chapter. The ball should also roll

as it bounces. This is another natural movement for a thrown ball. The

problem in this case is that it can't roll on its

pivot point, because we moved the pivot point to the

bottom of the ball for squash and stretch. We can't move the pivot

point back to the center, because we needed it where we put it. We

can't add another pivot point, because it can only have one. (Really? Any more helpful roadblocks?) So what do we do? We can

use a modifier that will act like a pivot

point: the XForm modifier.

Project Exercise 7: Adding a roll with

the XForm modifier

- Make sure that Auto Key is turned off.

Select the ball. Add an XForm modifier

to the ball with the menu sequence in the text, or with the Modifier

List, which is more memorable. (You should know both methods exist, and

use whichever you like.) Note that the XForm object has two

sub-objects: Gizmo and Center.

- Expand the XForm item in

the modifier stack, and select its Center sub-object.

- Click the Align tool, then click the ball.

You will see a dialog box. Make sure that all three axes

(x, y, and z) are checked. Click the the choice that

says Center under Target Object, and click OK.

The text pauses to make it clear that an object can have

only one pivot point. You have not added another

pivot point, you have just added a center point to

the object that it can rotate around. (I wonder if there is some judge

watching us to make sure we don't violate a copyrighted feature or some

such.)

So, now that you have the XForm modifier configured, you

need to use it. Continue on page 126.

- Turn on Auto Key. Click the Select

and Rotate tool.

- Click the XForm's Gizmo sub-object. The

text reveals that this is necessary to rotate around the XForm center

instead of the ball's pivot point (default).

Before you move ahead, think! Which way should the ball rotate? Which

viewport should you use to rotate it? I have seen too many balls spin

backwards. Don't do that.

- Put the time slider at frame 100 (the last frame). Rotate

the ball 360 degrees on its y-axis. (You may want to use the transform

type-in box for this.) Click the XForm object to leave sub-object mode,

and test the animation.

Question 2: Explain, in

your own words, why the XForm modifier was needed for this exercise.

This section of the text ends with an overview

of how to edit any of the keyframes used above.

Project: anticipation and momentum in a thrown

knife

Chapter 6 contains a series of exercises to

animate a knife thrown at at target. Begin as indicated on page

129, by copying the project file to your hard drive, and

setting the project root folder.

Project Exercise 1: Blocking the scene

- Open the start file. Move the time slider to frame

30, and turn on Auto Key.

- Move the knife into the target

as illustrated at the top of page 130. I had to move it down a bit as

well as horizontally to make it look right.

This is the first time you will have seen that objects in 3DS Max can

easily penetrate each other. Up to now, you have been

guided around that fact.

- Move the time slider to frame 15 and move

the knife higher in the scene, as

though it was at the peak of an arc.

The text offers no measurement for this, so make a guess

about a good z-axis value. The text does not show

you a good trick until later. You should know about it here. Do this:

- Open the Display

panel on the Command panel set.

- Scroll down to the Display Properties

rollout.

- Turn on the checkbox for Trajectory.

- You should see a red line on the screen.

Question 3: The red

line is the knife's trajectory. What information does this line give

you visually?

- The step shows you how to increase or decrease the number

of frames in a scene. (This is a very important skill

to have, so learn the location and use of this

button.) Click the Time Configuration button. (You

will find it near the Viewport Navigation Controls, the fifth

button from the bottom right corner of the workspace, unless they have changed it again.)

Once the Time Configuration window is open, find the End Time

field. The default value is 100 (frames). Change its value to 30.

Note that the End Time value will match

the Length value (30), and the Frame Count

value will be one more (31). Click OK to save this setting. This is a

useful technique for lengthening or shortening the number of frames in

a scene. Remember it, because you will use it again.

- The text asks you to play the animation, and to watch for

the default ease out and ease in at

the ends of the knife's path. This step also tries to provide a plan

for the next several steps, but there is a typo

in the way. Let's assume that we were just told that the knife should start moving at frame 10, not

frame 0. To make this correction, open the Curve Editor.

Find the x, y and z Position tracks in the Controller

window, and use Ctrl-click to select all three of

them. (Actually, they were all selected when I opened the curve editor.)

- Drag a marquee selection around the keyframes

at frame 0. Change the Select and Move tool

on the Curve Editor toolbar to the Horizontal Move

tool and use it to move the selected keyframes to frame 10.

Why use the Horizontal Move tool? Because you only want to move those

keyframes in time. The Horizontal Move tool is supposed

to constrain movement to the time axis, leaving the values on the

position axes unchanged. Well, that was a good idea in earlier versions

of the program. When I tried it this time, I found that the mouse would

move the keys vertically anyway. When you do it, note the vertical

value of one of the keys. Drag all the keys at once, but try to set

them down in the same relative vertical position at Frame 10.

- The action in step 6 changed the length

of the action. The new middle frame is 20, not 15.

Use the method in step 6 to move the keyframes

currently at frame 15 to frame 20.

The text introduces another "new" concept on page 132: trajectories.

We have already touche on it. In 3DS Max, a trajectory is the path an object takes

through a scene, made visible. The trajectory of the

knife in this scene is illustrated in the images at the bottom of page

132. To see a trajectory, select the Motion panel,

and click Trajectories. I told you to do it earlier

because it makes setting the path much easier.

On page 133, you are told to click the Sub-Object

button on the motion panel to get to the Key subobjects for the

trajectory. There is a step missing. You have to

click the Trajectories button first, then click the Sub-Object button.

(By default, my computer had the Parameters button

clicked, which was a problem until I realized what to do). Use the

procedure on these two pages, moving the key frames as subobjects, to

experiment with adjusting the vertical rise in the knife's path.

Knives that are thrown for any distance tend to spin.

The text continues the lesson by adding a rotation to

the knife. Again, plan this! Which viewport and which axis to rotate on?

Project Exercise 2: Adding rotation

- Move the time slider to frame 30, and

select the Select and Rotate tool. Make sure the Auto

Key feature is on. Select the knife

and rotate it on its y-axis by 443

degrees. (If you have Angle Snap turned on, 445 degrees will

also be fine.) The change in degrees is positive,

which means the knife rotates counter clockwise in the camera's current

view.

- Open the Curve Editor. Find and select the x, y,

and z Rotation tracks. This brings up an interesting point.

The Curve Editor shows rotation on the x-axis, not

the y-axis.When the knife rotates correctly, it rotates on

the y-axis and through the x-axis.

Refer to the exercise above for the method you should use to move the

keyframes at frame 0 to frame 10. Turn off

Auto Key when you have done so.

- Play the animation as instructed. You

still have an ease in and ease out,

which are not appropriate here. Why is this a step?

You need to learn to look for things to fix or

improve. You should always do this as a troubleshooting

step.

- Okay, they have been complaining about the ease in and ease

out that you get by default. It is time to correct that for this model.

Several sub-steps here.

In the Curve Editor, select the x-Position track.

Select all the keyframes on that track. Switch the

tangency for all those keyframes to Linear.

Select the z-Position track. Use the handles

on the individual keys (they appear when each key is selected)

to adjust the curve to be more like the reference illustration

in the middle of page 134.

- The authors provide more tweaks to the animation in this

step and the next. Try them, but be aware that you may not see the

improvement that the authors expect in this short animation. There is an error here, but I will address it at the

end of the project.

A person who throws a knife tends to move their hand backward

before moving it forward. This movement is referred to as anticipation.

Even though there is no hand in the scene at this time, we will add an

anticipation to the knife's movement.

Project Exercise 3: Adding anticipation

- Move the time slider to frame 0. Open the

Curve Editor and select the x-Rotation track for the knife. Click the Add

Keys button. Add a keyframe at frame 0. (Note,

in the image on page 135, the time slider is in the wrong place.)

- Select the Move tool as instructed, and

click the keyframe at frame 10. In

the Editor's Key Stats area, change the value of that

key to 240. This will begin the process of animating

the knife before the throw.

- The tangent at frame 0 is correct. Change the tangent

at frame 10 to Linear. Play

this animation and try to see why the authors don't

like it.

- Use the keyboard command to undo your

last change: Ctrl-Z. (The authors say you may have to

hit it more than once. I had to hit it twice.) Change the Move

tool to the Vertical Move tool. Select the In

tangent for keyframe 10. The In

tangent is the handle on the left

side of a keyframe. (The Out tangent would be the

handle on the right side of a keyframe.) You may have

to scroll the Curve Editor window to find it.

- Hold a shift key down as you drag

the keyframe's In tangent down to make the curve

resemble the one shown at the top of page 136. If you look carefully at

the image on that page, you will see that the authors pulled the handle

down and to the left a bit.

- Play the animation. If yours looks as bad

as mine did, you may realize that you need to adjust the other

Bezier control for the key at frame 10 as well. The authors did this,

but they did not mention it. Do so, so the knife continues to move with

some realism.

- Save again, to avoid problems.

Project Exercise 4: Follow-Through

- This next part of the project leads up to a transfer of momentum

from the knife to the target that moves the target (rocks it) just a

bit. In this exercise, you will add some frames and work on the knife.

In step 1, open the Time Configuration window again,

and change the End Time value to 45.

As the text explains, this will add fifteen frames to the end of the

current animation.

- Select the knife. Move the time

slider to frame 30. Open the Curve

Editor. Select the x-Position track for the

knife. Add a keyframe using the methods above at frame

35.

- The authors ask you to check the value of

the new keyframe by looking at the type-in boxes in

the Curve Editor. In their case, the value was about -231,

and they advise changing it to -224 (a difference of

7), to sink the knife farther into the target. My initial value was

very different, and yours may be as well. Adjust your

value up and down a bit to get a

depth into the target that you like, making sure that the knife is not

bouncing out of the target.

- Check the animation to make sure the knife

is moving as desired. You may want to try adding just a little

bounce here. A very small one. How? Pull the Bezier handle

for the last key so there is just a little bump in the curve between

the keys at 30 and 35. (A bump goes up, a dip goes

down. Yes, more vocabulary.)

- The authors want to add a bit of follow-through

(after the main action) rotation to the knife. Select

the x-Rotation track in the Curve Editor. Add a key

on this curve at frame 35. Note the change the

authors used between their keys at frames 30 and 35,

and adjust the value of your key at frame 35 by a similar amount. The

effect may not be noticeable.

- Save again.

Project Exercise 5: Momentum

This last part of the project in the text addresses another

transfer of momentum to the target. The target has to move

a bit, being pushed back by the knife's mass. If you have a feeling for

the physics of the situation, you can imagine what has to happen.

However, what happens if we animate just the target? Not good: the

knife has to move as well if it is in the target. We have to

animate the target and the knife together, which takes us to a hierarchy.

- Move the time slider to frame 30. Click

the Select and Link tool. Select the knife,

and link it to the target by dragging a line from the

knife to the target. (We do not want them linked in a hierarchy before

this frame.) This will make the knife a child object

of the target, which means the knife will move along with the target.

- Move the time slider to frame 34. Turn on

Auto Key. Choose the Select and

Rotate tool. Rotate the target about 5

degrees back, and be glad that the authors already moved the

target's pivot point.

- Open the Curve Editor. Select the y-Rotation

track for the target. Select the keyframe

at frame 0, and move it to frame

30. Next, shift-drag (copy) that keyframe

from frame 30 to frame 37. In both of these

operations, be careful not to change the value

(vertical position) of the original or copy frame.

- Change the tangent at frame 30

to Fast.

- Select the y-Rotation track for the target

again. Use Add Key to add keyframes

at frame 40 and frame 44. (This

seems like nonsense, since there are only 41 frames in the animation.)

Use the Vertical Move tool or the Value

entry field to set the value of the key at frame

40 to about 1.7.

- Choose the Select and Move tool. Move the

time slider to frame 37.

Move the target "just a bit" on the x-axis.

This is to show that the knife not only rocked the

target, it pushed it back a little. Open the Curve

Editor again, and select the x-Position curve

of the target. Next, select the keyframe

at frame 0, and move it to frame 30.

Change the tangent for frame 30 to Fast.

- Save the file incrementally.

Project Exercise 6: Another Tweak

Presently, the knife continues rotating even

after it has penetrated the target. If the target were plastic foam,

maybe it would. If the target is made of anything else, this is not

realistic. This is not in the book. It is my

requirement for completing the exercise.

- Select the knife.

- Turn on Auto Key.

- Open the Curve Editor. The knife should

stop rotating at frame 29, not frame 30. Change the

last Rotation key in each axis so that it happens at frame 29,

with the same value that it currently

has in frame 29. Do not just move the key

horizontally, since this will keep the value that it currently has in

frame 30. Move it vertically as well, to stop rotation upon full

contact with the target.

- Save again, and play it

for me in the application.

|