|

|

NET 211 - Wireless Networking

Chapter 11, Managing a Wireless LAN

Chapter 12: Wireless Network Troubleshooting and Optimization

Objectives:

This lesson covers two chapters about related topics.

Objectives important to this lesson:

- Risks

- Security defenses for wireless LANs

- Tools to monitor a wireless network

- Maintaining a wireless LAN

- Troubleshooting interference

- Troubleshooting a WLAN configuration

- Troubleshooting wireless devices

Concepts:

Chapter 11

The author begins this chapter with another story that seems

unrelated to the chapter objectives. Then he comes out of nowhere with

a few pages about risk management. This topic is not even in

the listed objectives, so I have added it as point 1 above.

The text introduces us to some vocabulary, illustrated by a

story about someone who wants to buy new rims for his car. The story is

useful, but not necessary to understand the terms.

- Asset - information, hardware, software,

or people that we care about

- Threat - a potential form of loss

or damage; many threats are only potential threats

- Threat agent - a vector for the

threat, a way for the threat to occur; could be a person, an

event, or a program running an attack

- Vulnerability - a weak spot where

an attack is more likely to succeed

- Exploit - a method of attack

- Risk - the probability of a loss

The text tells us on page 395 that there are three options

when dealing with risks. Mr. Ciampa actually presents a longer list in

another book, so let's use that one. Some options are known by multiple

names:

- Avoidance, defense

- make every effort to avoid your vulnerabilities being exploited; make

the attack less possible, make the threat less likely to occur; avoid

risk by performing the activity associated with the risk with greater

care or in a different way

- Transference - in

general, letting someone else worry about it

In the ITIL model, this is included in the definition of a service:

"A

service is a means of delivering value to customers by facilitating

outcomes customers want to achieve without the ownership of specific

costs and risks."

A reader might misunderstand this statement, thinking that the customer

does not pay anything. That is not the case. An IT service provider

would assume the costs and risks of an operation

in return for the customer's payment for the service. This can be done in-house

or by outsourcing.

- Mitigation - this

method seeks to reduce the effects

of an attack, to minimize and contain the damage that an attack can do;

Incident Response plans, Business Continuity plans, and Disaster

Recovery plans are all part of a mitigation plan

- Acceptance - this

counter-intuitive idea makes sense if the cost of an incident is

minimal, and the cost of all of the other methods is too high to

accept; the basic idea here is that it costs less just to let it happen

in some cases

- Terminate - simply

stop the business activities that are vulnerable to a given threat; we

cannot be exposed to a threat if we do not do what the threat affects

The author moves away from the general discussion of risks to

discuss social engineering attacks. It begins with another

story about people simply asking for access to a building and an

office, and making a request for a password change. A primary aspect of

social engineering is all about asking people for information

they see no reason to keep secret.

Psychological Approaches

The

following is a list of six attitudes/approaches a social engineer might

take when making a request for a password change. The

following is a list of six attitudes/approaches a social engineer might

take when making a request for a password change.

- Authority - pretend to be someone who has the right to make

the request

- Intimidation - in an oppressive environment, it may be easy

to use fear of what would happen if the request is not granted

- Consensus/social proof - tell a believable lie that others

have granted this request in the past

- Scarcity - tell the victim that you are short on time, or

you have to get this before it can't be done

- Urgency - tell the victim that you need this right now, and

that you will complete the red tape later

- Familiarity/Liking - act like one of the family, especially

one who appreciate the work the victim does for the company

- Trust - use details about the organization to make it seem

like you are a part of it

Someone who is practiced in manipulating people may be able to

choose between these approaches easily, based on the attitude of the

person on the other end of the phone, email, or messaging application.

A skilled operator may be able to do much more if the can manipulate

the person they are working on. Offering the person coffee, chocolate,

or other simple

gifts may make it easier to get them to do what you want.

Basic information about a target or a work site may be

obtained from documents on a public facing website, a Facebook site,

unshredded trash, or a phone call to the right person. Mr. Ciampa

offers this advice to prospective social engineers in another text:

- Ask for a little information from each of several people,

building your required knowledge base without alerting the victims

- Ask for what the victim is likely to be able to provide;

don't ask for something inconsistent with the victim's job or role

- Be pleasant and flattering, but in moderation

- Don't ask for so much that it raises suspicion about you

- Asking for help often triggers sympathy, thanking the

victim helps them believe they have done something good

The

best approach is to be a good actor, and to find the key to getting the

right response from the victim. Take a look at this blog

about acting. On the page that link leads to, there is some good

advice about portraying emotion. In the context of this discussion,

imagine yourself as the unsuspecting victim. Imagine the actress in the

photos as the grifter. Which of her expressions is the one you relate

to the most? Which is the one you want to help? Now, what do you look

like when you react in sympathy to her? You are communicating to her

that you are ready to hear and fulfill her requests. (If you can't see

her face clearly enough, follow the link to her page. The photos are

much clearer there, and her advice about showing emotion may be helpful

to you.) The

best approach is to be a good actor, and to find the key to getting the

right response from the victim. Take a look at this blog

about acting. On the page that link leads to, there is some good

advice about portraying emotion. In the context of this discussion,

imagine yourself as the unsuspecting victim. Imagine the actress in the

photos as the grifter. Which of her expressions is the one you relate

to the most? Which is the one you want to help? Now, what do you look

like when you react in sympathy to her? You are communicating to her

that you are ready to hear and fulfill her requests. (If you can't see

her face clearly enough, follow the link to her page. The photos are

much clearer there, and her advice about showing emotion may be helpful

to you.)

The text continues with a discussion of several other

approaches under this heading.

- Impersonation - An

attacker might impersonate anyone who might seem to belong in the

environment being surveilled or attacked. It is common to impersonate a

help desk employee when calling a victim. It is also common to

impersonate an employee, a delivery person, or a repair person when the

ploy calls for infiltrating a site.

- Phishing - Phishing is the solicitation of

personal or company information, typically through an official looking

email. Some variations on phishing:

- Spear phishing

- sending the email to specific

people, customizing it to look

like a message sent to them by an entity with some of their personal

information already

- Whaling - This

is spear phishing but it focuses on big (wealthy or data rich) targets.

- Pharming -

sending an email that takes the person directly to a web site (the

phisher's site) instead of asking the reader to follow a link

- Google phishing

- the phisher sets up a fake search engine that will send people to the

phishing web site on specific searches (presumably it returns real

search results on searches that would not lead to a page the phisher

has prepared)

- Spam - The section

on spam, unsolicited email, seems out of place in this discussion. Most

spam may only be looking for a customer, but some spam is sent with the

intent to steal, abuse, and sell the payment information that a person

might volunteer to provide.

- Hoaxes - In the

larger sense, all social engineering involves a hoax of some kind.

First the grifter finds a mark, then he tells the mark the tale, and

offers the deal. In the sense that the text means here, a hoax is

distraction from reality, such as when the attacker pretends that there

is a virus outbreak that is affecting the potential victim. It sets the

idea in the victim's mind that the attacker is trying to help and

should be assisted in his/her efforts.

- Typo squatting -

Most people are not great typists. The text explains that this is why

other people (the bad ones) register domain names that are similar but

not identical to real domains. They are hoping that the bad typists

among us will misspell a URL and find ourselves on their site instead

of the one we wanted, where we might volunteer information by trying to

log in with credentials that can then be abused, sold, or ransomed.

This technique is also called URL

hijacking by the text.

- Watering hole attack - The attacker determines that

targets in the company/agency often visit a particular web site, called

the watering hole in this scenario. It may be easier to infect that site than to attack the

individuals directly, and then to take advantage of the real target.

Physical Approaches

- Dumpster diving -

Attackers doing research on a company can learn a lot from the trash

the company discards. The text provides a table on page 73 with seven

suggestions about things to look for in a target's trash.

- Tailgating - The

concept behind tailgating is simple. Someone who does not have

authorization to pass through a secure entry point will gain access by

simply following an authorized person through it, or by waiting for the

door to open as someone exits through it. This might be done with or

without the knowledge or cooperation of the authorized person.

The author returns to thoughts about defenses against attacks

on page 398. He discusses three major

areas of defense: security policies,

training for users, and

security processes.

Security policies

Let me borrow from another course we are offering this term. That text

says that policies are inexpensive (they are just rules) but hard to implement,

because they have no effect if people do not comply with them. So, what

makes a good policy that people will follow? First, let's make a distinction

between four terms:

- Guideline - a guideline is a suggestion or a proposal that

people should follow, but may choose not to follow (if they are idiots)

- Policy - a policy is a plan that influences decisions;

a policy is a rule for making decisions and choosing

actions;

a policy needs to be understood by those meant to follow it because

it is a set of rules about what actions are acceptable

and what actions are unacceptable

- Standard - a statement of what must

be done to comply with a policy;

example: a standard might require that workstations bought for use in

a particular area (e.g. systems development) must be either of two specific

approved workstation models in order to comply with a policy that we

only purchase workstations from a short list from a contracted vendor;

a standard is typically more specific and narrow than

a policy, and tells you how do what you need to do so you don't

break the rules

- Practice - if a policy and its standards are still

a bit vague, a practice is a document that spells out more specifically

what we must do to be in compliance;

if standards are specific enough, a statement of practice

may not be necessary;

if different work areas, for example, must follow the rules in different

ways, they may each have a statement of practice to tell staff how to

comply in their jobs

Most texts have a list of requirements for a policy to be effective:

- Must be properly written -

understandable, relevant, clear

- Must be distributed - despite the

principle that ignorance

of the law is not an excuse, it is not sensible to expect staff to

comply with a policy they are not told about

- Must be read - if we email a policy

statement to all employees, does that guarantee that they all will read

it?

- Must be understood and agreed

to - it is frequently amazing that people will agree completely with a

policy as long as it applies to someone else, not them

- Must be uniformly applied - the rules

should be the same rules for everyone, or the policy will cause those

who must follow it to resent those who do not and those who make and

enforce the rules

Our text lists some purposes that a good security policy can serve. These

purposes support the the other two areas, as well, so let's take a look

at them:

- It can describe an intention and a direction that the organization

endorses, such as addressing security issues that caused a breach.

- It can be a formal notification of a risk, the organization's

choice about addressing that risk, and the expectations

the organization has for the actions of its staff

- It can promote awareness of security in general, which may

carry over to other activities.

- It can provide expectations to staff that their actions will

be monitored and those actions will have consequences

if the policy is not followed.

The text briefly discusses some steps frequently used in assessing the risks a

company is facing. This is covered in more depth in some texts, but the

author hits several high points. Typically, the steps would occur in this

order:

- Identify assets -

This means to create a list, to evaluate everything on it, and to

determine which ones we must, should, or may not protect. This step may also prioritize the assets in order of

importance to the company.

- Threat evaluation -

Some assets are threatened only by specific

threats, and some are much more

likely to occur than others. Which ones? The text asks us to

consider which threats are hazardous

to our company (not every company's list will be the same) and

which of those are the most dangerous.

- Vulnerability appraisal

- You need to look at each identified threat,

and determine which vulnerabilities

of which assets they actually

threaten. Where are we weak in protecting our assets?

- Risk assessment - The text is a bit vague about

assigning a value to a risk. If we can't measure it, it isn't science,

according to common wisdom, so let me introduce a formula from another

security text.

Let's consider some vocabulary that will help:

- Likelihood (L)- the probability that a threat

will be realized (actually

happen); in this method, it will be a number from .1 to 1.0. That's how

we measure probability, isn't it? 0 means it won't happen, 1 means it will, and anything in between is how

probable the event is.

- Value (V) - the monetary value of the asset; this

may be expressed as the income we lose if it is compromised and/or the

cost to replace the asset; alternatively, this may be a relative value compared to other

assets

- Mitigation (M) - the percentage of the risk that

we have protected against

- Uncertainty (U) - a fudge factor to express our

confidence (or lack of it) in the other numbers; this is expressed as a

percentage of the rest of the equation

The text observes that some risks have well known values. If we have to

calculate one, we

might do it like this:

Risk = (V * L) - (V * M) + U * ( (V * L) - (V * M) )

Assume the Value of an asset

is 200.

If the Likelihood of a threat

being realized is 60%, the

first term in this equation would be 200

* .6 = 120

Let's assume the amount of protection (Mitigation)

for this asset is 40%, so the

second term would be 200 * .4 = 80

The calculation for U depends on the rest of the equation. If we are

only 90% sure of our

Mitigation protection, the Uncertainty

for this calculation is 10%, but what do we do with it? We

multiply the uncertainty factor (10%) times the rest of the

equation. So the third term would be (

(V*L) - (V*M) ) * .1 = 40 * .1 = 4

So for this example, Risk = (200 * .6) - (200 * .4) + .1 * ( (200 * .6)

- (200 * .4) ) = 44

Another way of looking at this might be to say that V * L is our likely

loss if unprotected. V * M is the amount of the loss

that we are protecting. The difference between the two

is our probable loss, if we protect it. Finally, we add

a percentage to the probable loss to reflect our uncertainty in

the figures.

This method will give us a number for each risk, so we can compare them

to each other, and spend the most effort defending the right things.

- Risk mitigation - So what do we do to protect our

risks, now that they are rated and prioritized? It depends on the risk,

but the first step is usually to create security policies that

apply to each risk, sometimes multiple policies.

The text discusses several types of policies:

- Acceptable use policy - What are users allowed to do

with our assets, and just as importantly, what are they not allowed to

do? Everyone needs to be made aware of most policies, but this one is

critical.

- Password policy - A typical password policy sets

rules about the age at which they expire, their minimum

length, their required complexity, and how often a specific

password may be reused. The text reminds us that a policy can

contain more than the prompts a user will see when he/she is setting a

new password. Advice about what makes a good password and what

makes a poor password should also be included in the policy that is

communicated to users.

- Wireless policy - To relate the discussion back to this course,

a wireless policy might state when personal wireless devices may or

may not connect to the company network, matching rules for company owned

wireless devices, whether encryption is required, whether company information

may be stored or transmitted across what kind of network links. It is

often part of this policy that company information shall never be transmitted

across an unencrypted channel.

The text offers some general advice about writing a good

security policy on page 402. The point is that if we always trust

everyone, we have no security. If we never trust anyone, we have high

security, but very little ease of use of our systems. The best level of

security is usually one that allows people to do their job while

protecting the most sensitive assets with the strongest protection. One

way to do this is to make very sure we are allowing access only to the

right people, then to allow them full access. As the text points out,

there are extreme cases in which only the strongest security should be

used, but those are usually rare.

In addition to publishing and enforcing security policies,

another area of security is making users aware of security issues

through training and awareness programs. There should

be specific training for various activities, general awareness notices

and information for all employees, and updated information when systems

or policies are changed. The text offers a list of events that should

seen as appropriate times to give this kind of information to users:

- When hiring new staff

- When our systems are attacked

- When staff are promoted or change jobs

- When there are annual or quarterly events like retreats or

group meetings

- When software changes

- When hardware changes

The text moves on to discuss physical security for our

installations. To understand the discussion, we should make sure we

understand two phrases:

- Physical assets -

people, hardware, and supporting systems, which includes buildings and

their various parts

- Physical security -

protecting the organization's physical assets, which includes designing

and maintaining methods of protection

A thief who can steal your hardware can afford to take as much

time as he needs to harvest information from it, which makes physical

security as important as logical security.

The list of major physical controls below is a bit longer than

the one in our text. It covers a few more ideas.

- Walls, fences, and gates

- obvious barriers make it clear to people that they are not allowed to

walk beyond a certain point; gates are obvious points of access, but

they are also filter points if you require staff to show permission to

pass through them; these apply to external and internal environments

- Guards - putting a

guard on a gate, a door, or an asset allows you to set rules for

passage and usage that can be interpreted by a human being or referred

to an authorizing level of management

- Dogs - guard dogs

should probably appear as a subset of guards, whether they are working

with handlers or left to patrol a sealed environment; a dog can sense

things (noises, aromas) that a human guard cannot

- ID cards (badges) -

can be just a token or a photo ID, and may have a magnetic stripe, a

computer chip, or an RFID; ID cards are both a proof of authorization

and a problem: they need to be collected

when an employee leaves their job, regardless of who decided they were

leaving; the text describes tailgating,

the practice of passing through a door that senses an authorization

code by following someone who actually has authorization when you a) forgot yours, b) decided to be lazy, or c) are not authorized; it is the last

variation we worry about, so some secure centers require that everyone

passing a control point show their badge to the sensor to count heads;

the text mentions the use of ID operated turnstiles, which are effective in

metering traffic

- Locks - as

indicated above, some locks are opened with credentials; some locks require a key, and others require the intervention of an operator (e.g.

guard, receptionist); biometric

locks may be the most sophisticated locks: that means that unless they

are sophisticated they won't work well

- A door that stays locked

if the electronic lock fails has a fail-secure

lock.

- A door that becomes

unlocked if the electronic lock fails has a fail-safe lock. Since safe and secure are usually synonyms, this

makes no sense. You just have to know which is which.

- Cable locks -

Devices that are meant to be moved

are often built with little slots

that may be used with cables

which attach to desks, tables, or other structural features in the

workplace. The idea is that if something is locked down, it is less

likely to be stolen. It can still be stolen if the thief has a tool to

cut the cable, and if the cable is securing your docking station, that

means the thief may steal it as well as your laptop.

- Mantrap - a

vestibule or airlock with two doors that both lock if someone tries to pass

through the second door to a secure area and fails; the idea is to

alert security to a possible intrusion while containing the intruder

- Video monitoring -

allows recording of events, also allows fewer guards to watch over more

areas by watching several screens at once; this typically adds a delay

to response time, and may only be useful for collecting data after an

event

- Alarm systems -

commonly associated with the opening of a door, may be triggered by

sensors (motion, infrared, touch plates)

We return to wireless concerns on page 407. The author

observes that the tools generally included with a wireless device only

cover the senses of that device and will not give us much information

about the network itself or other devices on it. He recommends using

some features generally found on APs, such as the event log

that records the devices that have associated with that AP.

The rest of the chapter repeats information we have seen on SNMP

and introduces RMON,

a Remote Network Monitoring utility that uses the SNMP protocol. Some

advice is offered at the end of the chapter about maintenance of

network equipment, but it adds little to the ideas about wireless

networks.

Chapter 12

The last chapter we will cover in this course is Chapter 12, which is

about troubleshooting. The author tells us that we should begin troubleshooting

problems by determining which category the problem is part of. He lists

three major categories:

- RF interference - Although

we are concerned with any interference, such as the EMI that can be

generated by electric motors, for wireless LANs we care mostly about

interference in the RF bands.

Undesired signals from devices outside our network create what is usually

called noise. The text suggests

that we use a spectrum analyzer to find the RF noise

floor, the background RF level in a given environment. Our signals

must be stronger than this level if we are to hear them over that noise.

We should assume that there will always be a noise floor in any

environment.

The text remarks on page 431 that interference can come from other wireless

network devices, microwave ovens, cordless phones,

wireless video cameras, microwave links, and wireless

game controllers. This interference is mainly in the 2.4 GHz

band. There can also be interference in the 5 GHz band from newer

cordless phones, radar, perimeter sensors, and satellite

devices.

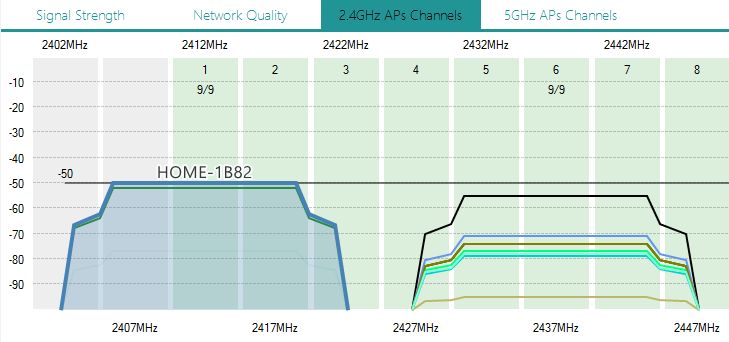

In the graphic above, taken with Acrylic Home, we see that there are

two APs on channel 1 (there are actually five), and at least six on

channel 6 (there are actually nine). In this case, the devices on channel

6 are interfering with each other a great deal because there are too

many at nearly the same signal strength. A solution to this problem

is addressed below.

The text refers to interference on specific portions of the RF band

as narrowband interference.

Such interference from television, radio, and satellite transmitters

typically does not affect wireless

frequencies, but it can do so if the signal is very

strong, as may happen when you are close to their transmitter.

This would be an argument for not

using wireless LANs inside a TV or radio station.

Wideband interference is when

a signal crosses over several frequencies, such as the entire usable

2.4 GHz band. As noted in the example above, you need to remove the

device causing the interference, move your LAN, or go to a wired solution.

When all else fails, remember that fibre optic network are immune to

EMI and RFI.

All-band Interference - The

text explains that there are special problems when you have trouble

with Frequency Hopping Spread Spectrum

(FHSS) systems because they

cover many frequencies over an entire band. This technology competes

with regular wireless LAN use. The text tells us there are proposals

to deal with this, but none are available as real solutions.

Weather Interference - As noted earlier in the text, weather

can refract an RF signal when it passes through weather that

causes the air to change in density, and precipitation

can cause RF deflection.

Troubleshooting advice:

- Use a spectrum analyzer to measure RF interference frequently.

Things change, so you should watch out for those changes. You will

not notice RF interference if you only use a packet sniffer.

- Look for interference from the devices listed above, but watch

out for new sources.

- Maintain a suitable fade margin so that your system does not fall

apart when a noise source suddenly increases in power.

- Separate antennas as much as possible, which will result in proper

coverage of desired areas, and less overlap of signals.

-

WLAN configuration

settings - Several settings that an administrator can set for

a wireless LAN can affect performance of that network. For example,

if all WLANs in a given area use the same channel by default,

there is a high probability of cochannel interference if they

are are all close to each other. Note the proper assignment of channels

in the two systems shown below. None of the adjacent WLANs uses the

same channels as another WLAN that it overlaps. In the case of the

5 MHz WLANs in the image on the right, none of the WLANs should have

a problem with adjacent channel interference. Each of the channels

used is far enough away from those being used nearby that there should

be no problems from this kind of interference.

The text mentions incorrect power settings, which are not available

on consumer equipment, only on commercial access points. Assuming

you are using configurable equipment, you may want to consider whether

increasing the power of an AP is worthwhile. If the AP can

reach the device, but the device cannot reach the AP, there

was no point to increasing the power. The text recommends a directional

antenna for the AP, which may help in the situation on pages 434

and 435. It would also help to have another AP on the far side

of the coverage area.

There are some bullet points on page 436 that concern factors that

can affect throughput on a network, in addition to those listed above.

- AP processor speed - OK, but what are we going to do about it?

- Distance from the AP - The obvious solution is to locate the

AP and move closer to it.

- Number of users on an AP - I have searched for an acceptable

answer to this one, but there seems to be disagreement about how

many users are too many.

- Packet size - As we discussed before, smaller packets are better

in most cases, and the network should manage that for us.

- Problems with the wireless device

(as opposed to problems from the other two sources) - The text discusses

some common problems and offers a few suggestions about resolving them.

- Near/Far - If a device is

very close to an AP (near) and another is significantly distant from

it (far), the near device may be transmitting a signal that is so

strong relative to the far device that the AP only notices the near

one. The text suggests moving the devices or changing their power

levels, but this is only practical when the devices are stationary.

Perhaps it would be desirable to place tables, desks, or seats in

a circle around the AP in order to equalize the service it can perform

for all users.

- Hidden Nodes - As described

previously, two devices may be located within range of an AP but not

in range of each other, which results in collisions at the AP when

both devices transmit. Again, the text addresses a solution that applies

to a workplace with static locations. The best solution offered is

to ad another AP for more coverage.

- Windows Connection - The

text presents a set of steps that a client on a Windows device will

go through when connecting to an AP. This is interesting, but not

very useful for troubleshooting. A possible exception is the note

about APIPA

addressing on the bottom of page 439. These are special addresses

in a range that is otherwise never used, that are self assigned when

a DHCP server cannot be reached. This feature needs to be turned on

for a client to produce such an address, but it could be turned on

as a way to notice when your DHCP server is not providing addresses

to clients.

- Troubleshooting steps -

You can't attach to an AP if your device and the AP don't speak a

common protocol.

Make sure the preshared key is correct.

If the AP filters on MAC addresses, it will exclude any device whose

MAC address is missing or entered incorrectly.

If the device has a switch to turn off its WiFi system, make sure

the switch is set to ON. The ON and OFF positions are not clearly

marked on most devices.

|